It’s a common held opinion that raising corporation tax is the worst thing for the economy, but is this actually true?

A low corporation tax is a great way to attract foreign direct investment and raise GDP. For example, in the 1990’s Ireland reduced its corporate tax rate to 12.5%. This attracted large, tax sensitive multi-national electronics companies (Intel, Dell, Apple) and pharmaceutical companies (Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson). Between 1996 and 2022 Ireland’s GDP grew by an average 9.4% per year, and in 2023, Ireland’s GDP per capita was €145,000: the highest in the world!

However, Ireland’s Economy isn’t as Rich as you think. The average income is only €41,000, which is less than a third of the GDP per capita figure. If we look at Actual Individual Consumption (AIC), we see that Ireland is in the bottom half of the EU: between Romania and Poland.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and, in particular, GDP growth, is the favourite of many economists for measuring the state of the national economy. However, GDP includes corporate investments and exports, which don’t contribute to the local economy. Companies like Apple, Amazon and Google use double taxation treaties (ensuring they are only taxed once) to claim most of their profits come from their (low tax) Irish R&D subsidiary.

For example, iPhone sales are counted as exports (and GDP), but profits are repatriated abroad; so they don’t contribute to the Irish economy. In 2018, the IMF calculated that 1/4 of the Irish growth came from iPhone sales, and, in 2017, Apple accounted for 1/5 of the Irish GDP. This kind of investment and accounting does not benefit the local population.

Of course, the corporation tax collected from these companies has contributed to the government revenue. Between 2001 and 2017, Irish Corporation Tax accounted for between 10.3% and 16.4% of government revenues. Across the EU in 2021, the Annual Report on Taxation reveals that corporate income tax accounted for only 7.1% of total revenues. Compared with the US, where the latest Monthly Treasury Statement shows that corporation tax provides 9.48% of government revenue.

Across the EU, over the last decade, there has mostly been a constant decline in the rate of corporate income tax. The average top tax rate on corporate income at the beginning of 2023 stood at 21.5%; more than 2 percentage points lower than in 2009. Lowering corporation tax to attract companies is a race to the bottom.

However, contrary to expectations, higher levels of effective marginal taxation (used by businesses to assess the return on investment) are actually associated with higher levels of investment in R&D.

Despite the evidence and EU’s Code of Conduct on Business Taxation‘s efforts to reduce the negative effects of tax incentives, effective marginal tax rates (the measure of the tax burden on a hypothetical investment project) have fallen from about 21.1% in 2008 to 15.8% in 2022.

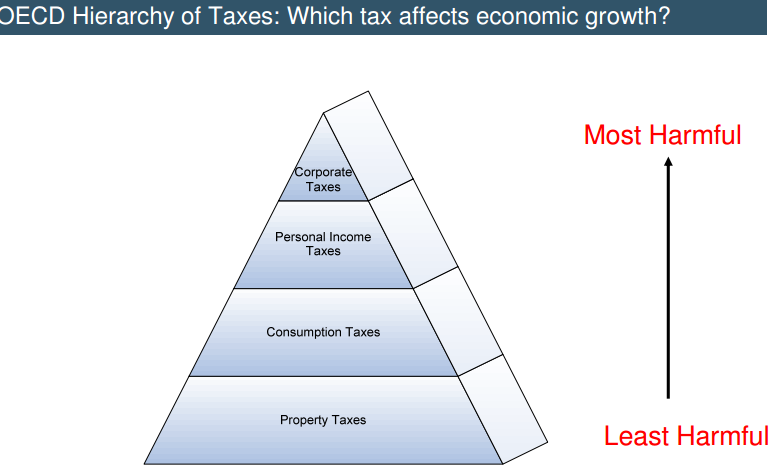

So why the focus on reducing corporation tax? Why is raising corporation tax considered the worst thing for the economy? Ireland’s Tax Strategy group’s 2018 review of corporate taxation references the 2008 OECD Taxation and Economic Growth Working Paper No. 620 in it’s creation of the OECD Hierarchy of Taxes pyramid.

The OECD Taxation and Economic Growth Working Paper No. 620 concludes that “Corporate taxes are found to be most harmful for growth, followed by personal income taxes, and then consumption taxes. Recurrent taxes on immovable property appear to have the least impact.” These two sentences, in the single paragraph abstract of the paper, appear to be the basis for the Irish government’s focus on minimising corporate taxes. However, the same paragraph also states that “reduced rates of corporate tax for small firms do not seem to enhance growth“. Clearly, just reading the entire abstract, never mind the 43 page (excluding appendices) working paper would suggest that there was more to corporate taxation than the simple hierarchy used by the Irish Tax Strategy Group.

The paper actually focuses on “the effects of changes in tax structures on GDP per capita“. Taxes are aimed at financing public expenses, but are also used to promote other objectives. So tax cuts are used as incentives, but it is simultaneously necessary to maintain tax revenues by increasing tax elsewhere. The paper spends a lot of time explaining how difficult it actually is to make these kinds of assessments, but it ultimately concludes that if tax cuts or increases don’t change behaviour, then those taxes can be safely increased. Likewise, if tax cuts or increases do change behaviour, then those taxes can be decreased.

Since changes in property tax are seen to have the least impact on behaviour these taxes can be increased (because they would cause the least harm). Since corporations are seen to frequently make investment decisions, changing these taxes are likely to have the greatest impact on behaviour (and therefore cause the most harm).

The reality is that higher corporate taxes don’t harm the economy. The US has one of the highest corporate tax rates in the world, and this has hardly had a negative impact on the economy. In the EU, contrary to expectations, countries with higher corporate tax rates actually have more investment in R&D. Lower corporate tax rates do attract large multi-nationals that can easily move intellectual property around. This may increase GDP and corporate tax revenues, but it does little to contribute to the country’s economy.

Globally, lower corporate tax rates have a negative impact by encouraging a race to the bottom.

What do you think?